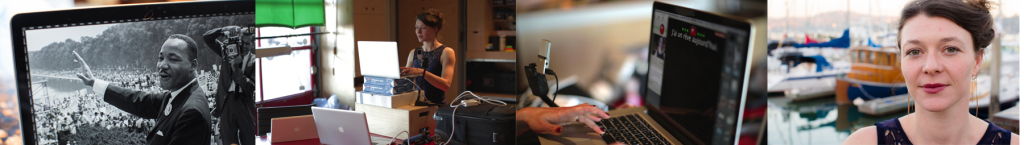

Martin Luther King’s famous “I have a dream” speech poses a challenge when translating to other languages (video in original English). As with all powerful language, the act of translation causes us to interpret the words. Marie Walburg Plouviez interpreted and recorded this historic speech: “I have a dream” in French, and in doing so, shared with us some of the implications of a French interpretation.

In English, “I have a dream” in the present tense can only refer to a vision for the future (rather than the more common meaning of dream, “a series of thoughts, images, and sensations occurring in a person’s mind during sleep”). This phrase is often translated into french “J’ai fait un rêve” using the verb “faire,” which translates literally as “I make a dream” or “I am doing the dream.” Another approach is to use the present tense with the verb “rêver” (“to dream”). “Je rêve” literally “I dream.” Marie uses three different translations to reinforce different connotations. The third creates the feeling of immediacy with the translation “J’ai un rêve aujourd’hui” using the verb “avoir” (“to have”).

We are enthralled by beautiful language. Even more so when the language is rich in meaning and purpose. Part of what makes this speech powerful is the repetition of the word “dream” in multiple contexts. Martin Luther King starts by evoking “the American dream.” Then he repeats the phrase “I have a dream” and “I have a dream today.” These two phrases transform the vision from the almost fantasy of Mississippi as “an oasis of freedom and justice” to a call to action that we make this vision happen within our lifetime. He conveys urgency with a vision that his four little children “will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.”

Few speeches have captivated the mind and the heart so completely as Martin Luther King’s I have a Dream speech, from August 28th, 1963. Last year we provided a Spanish translation with English recording, and this year we continue the tradition with French recording and translation of phrases from an excerpt of the speech.

In our interview with Marie, she refers to Le Monde’s interpretation. Along with their 2013 article, you can watch the full video with French subtitles.

Our mission at Mightyverse is to provide a place where all languages are equal, yet we celebrate their differences and richness of expression. As is so often the case, the translation can take the language into directions not anticipated and through the effort of poetic interpretation can make the language come alive anew.